Geshe Ngawang Wangyal: Difference between revisions

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

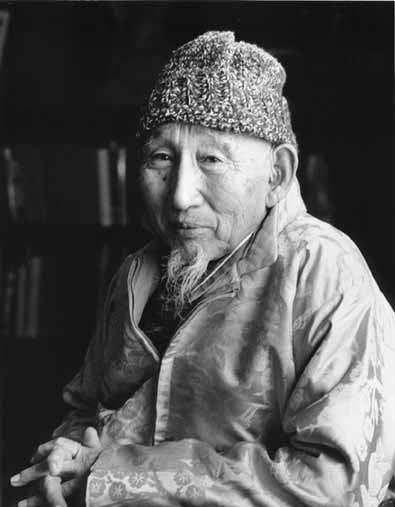

[[Image:Geshe wangyal.jpg|frame|'''Geshe Ngawang Wangyal''']] | [[Image:Geshe wangyal.jpg|frame|'''Geshe Ngawang Wangyal''']] | ||

'''Geshe Ngawang Wangyal''' ([[Wyl.]] ''dge bshes ngag dbang dbang rgyal'') (1901-1983) — a Kalmyk-Mongolian [[lama]] who was the first to come to America and teach in 1955. He established the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center in 1958 in New Jersey as the first [[Tibetan Buddhism|Tibetan Buddhist]] Dharma centre in the West. | '''Geshe Ngawang Wangyal''' (Tib. དགེ་བཤེས་ངག་དབང་དབང་རྒྱལ་, [[Wyl.]] ''dge bshes ngag dbang dbang rgyal'') (1901-1983) — a Kalmyk-Mongolian [[lama]] who was the first to come to America and teach in 1955. He established the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center in 1958 in New Jersey as the first [[Tibetan Buddhism|Tibetan Buddhist]] Dharma centre in the West. | ||

Professor [[Robert Thurman]] writes: | Professor [[Robert Thurman]] writes: | ||

:In | :In Geshe Ngawang Wangyal's presence it was hard to speak, my knees felt weak and my stomach unsettled. Yet the amazing thing was that Geshe Wangyal himself seemed as if he were not there. He had nothing to do with me, to me, or for me. He seemed fully content and unconcerned for himself. When I couldn’t find “him,” I was forced to ask myself, where is this “me” I’ve been pursuing? At twenty-one years old, after dropping out of school, leaving a new marriage, barely able to take care of myself, I felt a hint of something beyond myself. | ||

:Geshe Wangyal was unlike anyone I had ever met. As a teenage monk he had nearly died of typhoid in the hot Black Sea summer. His mother heard that the monks had given him up for dead, so she came to the monastery and spent three days sucking the pus and phlegm out of his throat and lungs to keep him from suffocating. When he awoke, the first thing he was told was that she had succumbed to the disease she saved him from and died on the very day he recovered. He was appalled when he observed that though he felt grief at the news, another current in his mind would not let him think of anything else except his overwhelming thirst after his ten-day fever. Noting this dreadful degree of selfishness, he resolved then and there to give his last ounce to freeing himself and others from such involuntarily selfish impulses. I had never encountered such unconditional compassion directly in my entire life.<ref>Robert Thurman, ''Inner-Revolution: Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness'', Penguin, 1999.</ref> | :Geshe Wangyal was unlike anyone I had ever met. As a teenage monk he had nearly died of typhoid in the hot Black Sea summer. His mother heard that the monks had given him up for dead, so she came to the monastery and spent three days sucking the pus and phlegm out of his throat and lungs to keep him from suffocating. When he awoke, the first thing he was told was that she had succumbed to the disease she saved him from and died on the very day he recovered. He was appalled when he observed that though he felt grief at the news, another current in his mind would not let him think of anything else except his overwhelming thirst after his ten-day fever. Noting this dreadful degree of selfishness, he resolved then and there to give his last ounce to freeing himself and others from such involuntarily selfish impulses. I had never encountered such unconditional compassion directly in my entire life.<ref>Robert Thurman, ''Inner-Revolution: Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness'', Penguin, 1999.</ref> | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

<small><references/></small> | |||

==Publications== | ==Publications== | ||

*Geshe Wangyal, ''The Door of Liberation: Essential Teachings of the Tibetan Buddhist Tradition'' | *Geshe Wangyal, ''The Door of Liberation: Essential Teachings of the Tibetan Buddhist Tradition'' (Wisdom Publications: 1973, republished in 1995) | ||

[[Category: Contemporary Teachers]] | [[Category: Contemporary Teachers]] | ||

[[Category: Gelugpa Teachers]] | [[Category: Gelugpa Teachers]] | ||

Latest revision as of 08:30, 22 June 2021

Geshe Ngawang Wangyal (Tib. དགེ་བཤེས་ངག་དབང་དབང་རྒྱལ་, Wyl. dge bshes ngag dbang dbang rgyal) (1901-1983) — a Kalmyk-Mongolian lama who was the first to come to America and teach in 1955. He established the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center in 1958 in New Jersey as the first Tibetan Buddhist Dharma centre in the West.

Professor Robert Thurman writes:

- In Geshe Ngawang Wangyal's presence it was hard to speak, my knees felt weak and my stomach unsettled. Yet the amazing thing was that Geshe Wangyal himself seemed as if he were not there. He had nothing to do with me, to me, or for me. He seemed fully content and unconcerned for himself. When I couldn’t find “him,” I was forced to ask myself, where is this “me” I’ve been pursuing? At twenty-one years old, after dropping out of school, leaving a new marriage, barely able to take care of myself, I felt a hint of something beyond myself.

- Geshe Wangyal was unlike anyone I had ever met. As a teenage monk he had nearly died of typhoid in the hot Black Sea summer. His mother heard that the monks had given him up for dead, so she came to the monastery and spent three days sucking the pus and phlegm out of his throat and lungs to keep him from suffocating. When he awoke, the first thing he was told was that she had succumbed to the disease she saved him from and died on the very day he recovered. He was appalled when he observed that though he felt grief at the news, another current in his mind would not let him think of anything else except his overwhelming thirst after his ten-day fever. Noting this dreadful degree of selfishness, he resolved then and there to give his last ounce to freeing himself and others from such involuntarily selfish impulses. I had never encountered such unconditional compassion directly in my entire life.[1]

Notes

- ↑ Robert Thurman, Inner-Revolution: Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness, Penguin, 1999.

Publications

- Geshe Wangyal, The Door of Liberation: Essential Teachings of the Tibetan Buddhist Tradition (Wisdom Publications: 1973, republished in 1995)