Wheel of Life: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

m (Removed invalid link to Rigpa.org page) |

||

| (16 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image: | [[Image:SRT34wheel of life.jpg|thumb|350px|'''The Wheel of Life''']] | ||

'''Wheel of Life''' (Skt. ''bhavacakra''; [[Wyl.]] ''srid pa'i 'khor lo'') — a traditional representation of the samsaric cycle of existence. Also translated as ''wheel of existence'', or ''wheel of cyclic existence''. | '''Wheel of Life''' (Skt. ''bhavacakra''; Tib. སྲིད་པའི་འཁོར་ལོ་, ''sipé khorlo'', [[Wyl.]] ''srid pa'i 'khor lo'') — a traditional representation of the [[samsara|samsaric cycle of existence]]. Also translated as ''wheel of existence'', or ''wheel of cyclic existence''. | ||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

[[Jeffrey Hopkins]] writes: | [[Jeffrey Hopkins]] writes: | ||

:The diagram, said to be designed by Buddha himself, depicts an inner psychological cosmology that has had great influence throughout Asia. It is much like a map of the world or the periodic table of elements, but it is a map of an internal process and its external effects.<ref>The Dalai Lama, ''The Meaning of Life'', translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 1.</ref> | :The diagram, said to be designed by [[Buddha]] himself, depicts an inner psychological cosmology that has had great influence throughout Asia. It is much like a map of the world or the periodic table of elements, but it is a map of an internal process and its external effects.<ref>The Dalai Lama, ''The Meaning of Life'', translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 1.</ref> | ||

[[Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche]] writes: | [[Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche]] writes: | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

==A Brief Explanation of the Diagram== | ==A Brief Explanation of the Diagram== | ||

The meanings of the main parts of the diagram are: | The meanings of the main parts of the diagram are: | ||

* The | * The centre of the wheel represents the [[three poisons]]. | ||

* The second layer represents positive and negative actions, or [[karma]]. | * The second layer represents positive and negative actions, or [[karma]]. | ||

* The third layer represents the [[six realms|six realms of samsara]]. | * The third layer represents the [[six realms|six realms of samsara]]. | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

[[The Dalai Lama]] writes: | [[The Dalai Lama]] writes: | ||

:Symbolically [the inner] three circles, moving from the | :Symbolically [the inner] three circles, moving from the centre outward, show that the three afflictive emotions<ref>An alternate translation of the [[three poisons]].</ref> of desire, hatred, and ignorance give rise to virtuous and non-virtuous actions, which in turn give rise to levels of suffering in cyclic existence. The outer rim symbolizing the twelve links of dependent arising indicates ''how'' the sources of suffering—actions and afflictive emotions—produce lives within cyclic existence. The fierce being holding the wheel symbolizes impermanence... | ||

:The moon [at the top] indicates liberation. The Buddha on the left is pointing to the moon, indicating that liberation that causes one to cross the ocean of suffering of cyclic existence should be actualized.<ref>The Dalai Lama, ''The Meaning of Life'', translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 42.</ref> | :The moon [at the top] indicates liberation. The Buddha on the left is pointing to the moon, indicating that liberation that causes one to cross the ocean of suffering of cyclic existence should be actualized.<ref>The Dalai Lama, ''The Meaning of Life'', translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 42.</ref> | ||

==A Detailed Explanation of the Diagram== | ==A Detailed Explanation of the Diagram== | ||

=== | ===Centre of the Wheel: The Three Poisons=== | ||

[[Image: | [[Image:Centre_of_wheel_of_life.jpg|frame|The centre of the Wheel of Life, featuring a pig, snake and bird representing ignorance, anger and desire]] | ||

[[Ringu Tulku Rinpoche]] writes: | [[Ringu Tulku Rinpoche]] writes: | ||

:Tibetans have a traditional painting called the Wheel of Life, which depicts the samsaric cycle of existence. In the | :Tibetans have a traditional painting called the Wheel of Life, which depicts the samsaric cycle of existence. In the centre of this wheel are three animals: a pig, a snake, and a bird. They represent the [[three poisons]]. The pig stands for ignorance, although a pig is not necessarily more stupid than other animals. The comparison is based on the Indian concept of a pig being the most foolish of animals, since it always sleeps in the dirtiest places and eats whatever comes to its mouth. Similarly, the snake is identified with anger because it will be aroused and leap up at the slightest touch. The bird represents desire and clinging. In Western publications it is frequently referred to as a cock, but this is not exactly accurate. This particular bird does not exist in Western countries, as far as I know. It is used as a symbol because it is very attached to its partner. These three animals represent the three main mental poisons, which are the core of the Wheel of Life. Stirred by these, the whole cycle of existence evolves. Without them, there is no [[samsara]].<ref>Ringu Tulku, ''Daring Steps Toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Tibetan Buddhism'', Snow Lion, 2005 page 30.</ref> | ||

===Second Layer: Positive and Negative Actions=== | ===Second Layer: Positive and Negative Actions=== | ||

The images in this layer vary in different paintings of the wheel. In the image shown here, the two half circles represent positive and negative actions, or [[karma]], that are motivated by the three poisons of ignorance, attachment/desire and aversion/anger. | The images in this layer vary in different paintings of the wheel. In the image shown here, the two half circles represent positive and negative actions, or [[karma]], that are motivated by the three poisons of ignorance, attachment/desire and aversion/anger. | ||

* The half-circle on the right shows positive or virtuous actions. Such actions are the means for attaining lives in the three | *The half-circle on the right shows positive or virtuous actions. Such actions are the means for attaining lives in the [[three higher realms]] of the gods, demi-gods and humans. | ||

* The half-circle on the left shows negative or non-virtuous actions. Such actions are the means for attaining lives in the three | *The half-circle on the left shows negative or non-virtuous actions. Such actions are the means for attaining lives in the [[three lower realms]] of the animals, hungry ghosts and hell-beings. | ||

===Third Layer: Six Realms of Samsara=== | ===Third Layer: Six Realms of Samsara=== | ||

The third layer of the wheel depicts the [[six realms]] of samsara. | The third layer of the wheel depicts the [[six realms]] of samsara. | ||

=== Fourth Layer: Twelve Links=== | ===Fourth Layer: Twelve Links=== | ||

The fourth layer of the wheel depicts the [[twelve nidanas|twelve links of interdependent origination]]. | The fourth layer of the wheel depicts the [[twelve nidanas|twelve links of interdependent origination]]. | ||

===The Monster Holding the Wheel: Impermanence=== | ===The Monster Holding the Wheel: Impermanence=== | ||

[[Jeffrey Hopkins]] writes: | [[Jeffrey Hopkins]] writes: | ||

:The wheel in the | :The wheel in the centre of the painting is in the grasp of a frightful monster. This signifies that the entire process of cyclic existence is caught within transience. Everything in our type of life is characterized by impermanence. Whatever is built will fall down, whatever and whoever come together will fall apart.<ref>The Dalai Lama, ''The Meaning of Life'', translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 3.</ref> | ||

[[The Dalai Lama]] writes: | [[The Dalai Lama]] writes: | ||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

:The Western poet Rainer Maria Rilke has said that our deepest fears are like dragons guarding our deepest treasure. The fear that impermanence awakens in us, that nothing is real and nothing lasts, is, we come to discover, our greatest friend because it drives us to ask: If everything dies and changes, then what is really true? Is there something behind the appearances, something boundless and infinitely spacious, something in which the dance of change and impermanence takes place? Is there something in fact we can depend on, that does survive what we call death? | :The Western poet Rainer Maria Rilke has said that our deepest fears are like dragons guarding our deepest treasure. The fear that impermanence awakens in us, that nothing is real and nothing lasts, is, we come to discover, our greatest friend because it drives us to ask: If everything dies and changes, then what is really true? Is there something behind the appearances, something boundless and infinitely spacious, something in which the dance of change and impermanence takes place? Is there something in fact we can depend on, that does survive what we call death? | ||

:Allowing these questions to occupy us urgently, and reflecting on them, we slowly find ourselves making a profound shift in the way we view everything. With continued contemplation and practice in letting go, we come to uncover in ourselves "something" we cannot name or describe or conceptualize, "something" that we begin to realize lies behind all the changes and deaths of the world.<ref>Sogyal Rinpoche, ''The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying'', Harper San Francisco, 2002, page 39.</ref> | :Allowing these questions to occupy us urgently, and reflecting on them, we slowly find ourselves making a profound shift in the way we view everything. With continued contemplation and practice in letting go, we come to uncover in ourselves "something" we cannot name or describe or conceptualize, "something" that we begin to realize lies behind all the changes and deaths of the world.<ref>Sogyal Rinpoche, ''[[The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying]]'', Harper San Francisco, 2002, page 39.</ref> | ||

===The Buddha and the Moon: Liberation from Suffering=== | ===The Buddha and the Moon: Liberation from Suffering=== | ||

Jeffrey Hopkins writes: | |||

:At the top right of the painting as we face it, the Buddha is standing with his left hand in a teaching pose and with the index finger of the right hand pointing to a moon... The moon symbolizes liberation. Buddha is pointing out that freedom from pain is possible... The intent of the painting is not to communicate mere knowledge of a process but to put this knowledge to use in redirecting and uplifting our lives.<ref>The Dalai Lama, ''The Meaning of Life'', translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 2.</ref> | :At the top right of the painting as we face it, the Buddha is standing with his left hand in a teaching pose and with the index finger of the right hand pointing to a moon... The moon symbolizes liberation. Buddha is pointing out that freedom from pain is possible... The intent of the painting is not to communicate mere knowledge of a process but to put this knowledge to use in redirecting and uplifting our lives.<ref>The Dalai Lama, ''The Meaning of Life'', translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 2.</ref> | ||

Ringu Tulku Rinpoche writes: | |||

:The Buddha showed the gradual way toward the cessation of suffering by means of the [[Noble eightfold path|Noble Eightfold Path]]. Again, this is a very basic teaching, yet it is not just a preliminary one. When examined deeply, it proves to cover the whole journey... The entire teaching of the Buddha is included in this path, which provides the basic guideline on how to work with and overcome the sources of suffering.<ref>Ringu Tulku, ''Daring Steps Toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Tibetan Buddhism'', Snow Lion, 2005 page 37.</ref> | :The Buddha showed the gradual way toward the cessation of suffering by means of the [[Noble eightfold path|Noble Eightfold Path]]. Again, this is a very basic teaching, yet it is not just a preliminary one. When examined deeply, it proves to cover the whole journey... The entire teaching of the Buddha is included in this path, which provides the basic guideline on how to work with and overcome the sources of suffering.<ref>Ringu Tulku, ''Daring Steps Toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Tibetan Buddhism'', Snow Lion, 2005 page 37.</ref> | ||

Sogyal Rinpoche writes: | |||

:All the spiritual teachers of humanity have told us the same thing, that the purpose of life on earth is to achieve union with our fundamental, enlightened nature... There is only one way to do this, and that is to undertake the spiritual journey, with all the ardor and intelligence, courage and resolve for transformation that we can muster.<ref>Sogyal Rinpoche, ''The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying'', Harper San Francisco, 2002, page 131.</ref> | :All the spiritual teachers of humanity have told us the same thing, that the purpose of life on earth is to achieve union with our fundamental, enlightened nature... There is only one way to do this, and that is to undertake the spiritual journey, with all the ardor and intelligence, courage and resolve for transformation that we can muster.<ref>Sogyal Rinpoche, ''The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying'', Harper San Francisco, 2002, page 131.</ref> | ||

==Further Reading== | ==Further Reading== | ||

*[[The Dalai Lama]], ''The Meaning of Life'', translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Wisdom, 2000 | |||

*[[Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche]], ''Gentle Voice'' #22, September 2004 Issue | *[[Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche]], ''Gentle Voice'' #22, September 2004 Issue | ||

*[[Geshe Sonam Rinchen]], ''How Karma Works: The Twelve Links of Dependent Arising'', Snow Lion, 2006 | *[[Geshe Sonam Rinchen]], ''How Karma Works: The Twelve Links of Dependent Arising'', Snow Lion, 2006 | ||

*[[Patrul Rinpoche]], ''[[The Words of My Perfect Teacher]]'' (Boston: Shambhala, Revised edition, 1998), page 96. | |||

*[[Ringu Tulku]], ''Daring Steps Toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Tibetan Buddhism'', Snow Lion, 2005 | *[[Ringu Tulku]], ''Daring Steps Toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Tibetan Buddhism'', Snow Lion, 2005 | ||

*[[Sogyal Rinpoche]], ''The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying'', Harper San Francisco, 2002 | *[[Sogyal Rinpoche]], ''[[The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying]]'', Harper San Francisco, 2002 | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

<small><references/></small> | <small><references/></small> | ||

==Internal Links== | |||

*[[Rice Seedling Sutra]] | |||

==External Links== | |||

*[http://www.rigpa.org/en/teachings/extracts-of-articles-and-publications/extracts-from-the-tibetan-book-of-living-and-dying/reflection-and-change.html Reflection and Change: From ''The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying'' (Chapter 3) by Sogyal Rinpoche] | |||

*[http://www.siddharthasintent.org/gentle/GVindex.htm#22 ''Gentle Voice'' #22, September 2004 Issue] | |||

*[http://www.himalayanart.org/pages/wheeloflife/index.html Wheel of Life outline page at Himalayan Art Resources] | |||

[[Category:Key Terms]] | [[Category:Key Terms]] | ||

[[Category:Destructive Emotions]] | [[Category:Destructive Emotions]] | ||

[[Category:Karma]] | [[Category:Karma]] | ||

[[Category:Three Realms]] | [[Category: Three Realms of Samsara]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:01, 23 September 2021

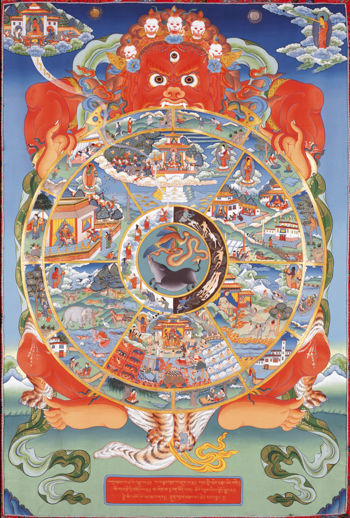

Wheel of Life (Skt. bhavacakra; Tib. སྲིད་པའི་འཁོར་ལོ་, sipé khorlo, Wyl. srid pa'i 'khor lo) — a traditional representation of the samsaric cycle of existence. Also translated as wheel of existence, or wheel of cyclic existence.

Overview

The Wheel of Life is a traditional representation of the samsaric cycle of existence.

Jeffrey Hopkins writes:

- The diagram, said to be designed by Buddha himself, depicts an inner psychological cosmology that has had great influence throughout Asia. It is much like a map of the world or the periodic table of elements, but it is a map of an internal process and its external effects.[1]

Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche writes:

- It’s quite a popular painting that you can see in front of almost every Buddhist monastery. In fact, some Buddhist scholars believe that the painting existed prior to Buddha’s statues. This is probably the first ever Buddhist symbol that existed...

- One of the reasons why the Wheel of Life was painted outside the monasteries and on the walls (and was really encouraged even by the Buddha himself) is to teach this very profound Buddhist philosophy of life and perception to more simple-minded farmers or cowherds. So these images on the Wheel of Life are just to communicate to the general audience.[2]

A Brief Explanation of the Diagram

The meanings of the main parts of the diagram are:

- The centre of the wheel represents the three poisons.

- The second layer represents positive and negative actions, or karma.

- The third layer represents the six realms of samsara.

- The fourth layer represents the twelve links of interdependent origination.

- The monster holding the wheel represents impermanence.

- The moon above the wheel represents liberation from the samsaric cycle of existence.

- The Buddha pointing to the moon indicates that liberation is possible.

The Dalai Lama writes:

- Symbolically [the inner] three circles, moving from the centre outward, show that the three afflictive emotions[3] of desire, hatred, and ignorance give rise to virtuous and non-virtuous actions, which in turn give rise to levels of suffering in cyclic existence. The outer rim symbolizing the twelve links of dependent arising indicates how the sources of suffering—actions and afflictive emotions—produce lives within cyclic existence. The fierce being holding the wheel symbolizes impermanence...

- The moon [at the top] indicates liberation. The Buddha on the left is pointing to the moon, indicating that liberation that causes one to cross the ocean of suffering of cyclic existence should be actualized.[4]

A Detailed Explanation of the Diagram

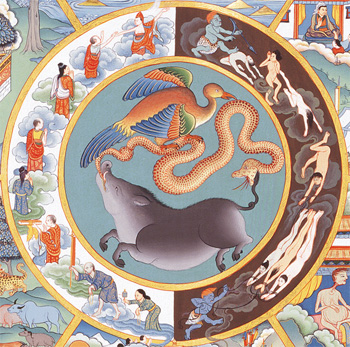

Centre of the Wheel: The Three Poisons

Ringu Tulku Rinpoche writes:

- Tibetans have a traditional painting called the Wheel of Life, which depicts the samsaric cycle of existence. In the centre of this wheel are three animals: a pig, a snake, and a bird. They represent the three poisons. The pig stands for ignorance, although a pig is not necessarily more stupid than other animals. The comparison is based on the Indian concept of a pig being the most foolish of animals, since it always sleeps in the dirtiest places and eats whatever comes to its mouth. Similarly, the snake is identified with anger because it will be aroused and leap up at the slightest touch. The bird represents desire and clinging. In Western publications it is frequently referred to as a cock, but this is not exactly accurate. This particular bird does not exist in Western countries, as far as I know. It is used as a symbol because it is very attached to its partner. These three animals represent the three main mental poisons, which are the core of the Wheel of Life. Stirred by these, the whole cycle of existence evolves. Without them, there is no samsara.[5]

Second Layer: Positive and Negative Actions

The images in this layer vary in different paintings of the wheel. In the image shown here, the two half circles represent positive and negative actions, or karma, that are motivated by the three poisons of ignorance, attachment/desire and aversion/anger.

- The half-circle on the right shows positive or virtuous actions. Such actions are the means for attaining lives in the three higher realms of the gods, demi-gods and humans.

- The half-circle on the left shows negative or non-virtuous actions. Such actions are the means for attaining lives in the three lower realms of the animals, hungry ghosts and hell-beings.

Third Layer: Six Realms of Samsara

The third layer of the wheel depicts the six realms of samsara.

Fourth Layer: Twelve Links

The fourth layer of the wheel depicts the twelve links of interdependent origination.

The Monster Holding the Wheel: Impermanence

Jeffrey Hopkins writes:

- The wheel in the centre of the painting is in the grasp of a frightful monster. This signifies that the entire process of cyclic existence is caught within transience. Everything in our type of life is characterized by impermanence. Whatever is built will fall down, whatever and whoever come together will fall apart.[6]

The Dalai Lama writes:

- The fierce being holding the wheel symbolizes impermanence, which is why the being is a wrathful monster, though there is no need for it to be drawn with ornaments and so forth... Once I had such a painting drawn with a skeleton rather than a monster, in order to symbolize impermanence more clearly.[7]

Reflecting on impermanence can start us on the path towards liberation.

Sogyal Rinpoche writes:

- The Western poet Rainer Maria Rilke has said that our deepest fears are like dragons guarding our deepest treasure. The fear that impermanence awakens in us, that nothing is real and nothing lasts, is, we come to discover, our greatest friend because it drives us to ask: If everything dies and changes, then what is really true? Is there something behind the appearances, something boundless and infinitely spacious, something in which the dance of change and impermanence takes place? Is there something in fact we can depend on, that does survive what we call death?

- Allowing these questions to occupy us urgently, and reflecting on them, we slowly find ourselves making a profound shift in the way we view everything. With continued contemplation and practice in letting go, we come to uncover in ourselves "something" we cannot name or describe or conceptualize, "something" that we begin to realize lies behind all the changes and deaths of the world.[8]

The Buddha and the Moon: Liberation from Suffering

Jeffrey Hopkins writes:

- At the top right of the painting as we face it, the Buddha is standing with his left hand in a teaching pose and with the index finger of the right hand pointing to a moon... The moon symbolizes liberation. Buddha is pointing out that freedom from pain is possible... The intent of the painting is not to communicate mere knowledge of a process but to put this knowledge to use in redirecting and uplifting our lives.[9]

Ringu Tulku Rinpoche writes:

- The Buddha showed the gradual way toward the cessation of suffering by means of the Noble Eightfold Path. Again, this is a very basic teaching, yet it is not just a preliminary one. When examined deeply, it proves to cover the whole journey... The entire teaching of the Buddha is included in this path, which provides the basic guideline on how to work with and overcome the sources of suffering.[10]

Sogyal Rinpoche writes:

- All the spiritual teachers of humanity have told us the same thing, that the purpose of life on earth is to achieve union with our fundamental, enlightened nature... There is only one way to do this, and that is to undertake the spiritual journey, with all the ardor and intelligence, courage and resolve for transformation that we can muster.[11]

Further Reading

- The Dalai Lama, The Meaning of Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Wisdom, 2000

- Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Gentle Voice #22, September 2004 Issue

- Geshe Sonam Rinchen, How Karma Works: The Twelve Links of Dependent Arising, Snow Lion, 2006

- Patrul Rinpoche, The Words of My Perfect Teacher (Boston: Shambhala, Revised edition, 1998), page 96.

- Ringu Tulku, Daring Steps Toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Tibetan Buddhism, Snow Lion, 2005

- Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, Harper San Francisco, 2002

Notes

- ↑ The Dalai Lama, The Meaning of Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 1.

- ↑ Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Gentle Voice #22, September 2004 Issue, page 3.

- ↑ An alternate translation of the three poisons.

- ↑ The Dalai Lama, The Meaning of Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 42.

- ↑ Ringu Tulku, Daring Steps Toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Tibetan Buddhism, Snow Lion, 2005 page 30.

- ↑ The Dalai Lama, The Meaning of Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 3.

- ↑ The Dalai Lama, The Meaning of Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 42.

- ↑ Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, Harper San Francisco, 2002, page 39.

- ↑ The Dalai Lama, The Meaning of Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 2.

- ↑ Ringu Tulku, Daring Steps Toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Tibetan Buddhism, Snow Lion, 2005 page 37.

- ↑ Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, Harper San Francisco, 2002, page 131.