Mount Everest

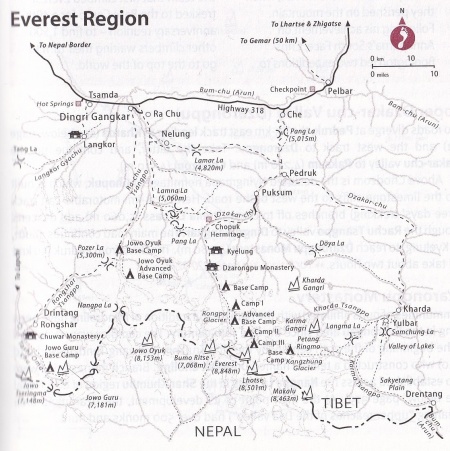

Mount Everest aka Chomolunga (Tib. ཇོ་མོ་གླང་མ) is a sacred mountain situated located at an elevation of 6,656 meters above the sea level. She is Earth's highest mountain above sea level, located in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas. The international border between Nepal (Province No. 1) and China (Tibet Autonomous Region) runs across its summit point.

Names

The Dalai Lama wrote,[1]

- Mount Everest, or as she is known in Tibet, Chomolounga. […] There is one class of people who frequent the mountains for the very reason that other people stay away from them. Meditators welcome the simplicity and quietness that abound in the mountains, for there they can meditate undisturbed. Since the practice of Buddhism involves seeing phenomena as empty of inherent existence, it is helpful for a meditator to be able to look into the vast, empty space seen from a mountain.

In the guide-text to the Béyul Khembalung presented to the 1936 expedition by the head lama at Rongbuk, Ngawang Tendzin Norbu aka the 10th Dzatrul Rinpoche, the name appears as Chha-mo-lang-ma, pronounced and transcribed elsewhere as Jomolanma. […] In one rather prosaic translation, Chomolungma simply means “The Peak Above the Valley”, and looking south from Rongpuk monastery to where Everest fills the head of the wide Rongbuk Glacier, this translation makes perfect sense. [2]

Description=

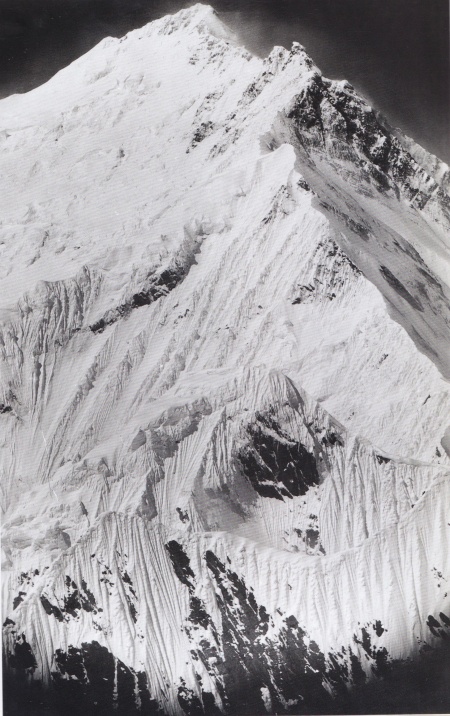

Stephen Venables describes it in the following way, ‘The magnificent height of Mount Everest, the summit of the highest range of mountains on earth, is the result of tectonic actions—the inconceivable powerful geologic force that moves the continental landmasses against each other. The landmass of India is forced against the landmass of Asia, and the Himalayan ranges are pushed up in between. The process continues inexorably to this day, lifting the entire Himalayan range by several millimeters each year. This range, which is really a complex skein of ranges, is the mightiest geographical feature of the earth’s surface. About half as long as the Atlantic is wide, it boasts more than a hundred peaks in excess of 24,000 feet (7315 m) above sea level and at least 20 of more than 26,000 feet (7925 m), which is higher than the highest mountains found anywhere else in the world. Seen from the moon, the range would be the frown on the face of our planet. It is also Asia’s “Great Barrier Ridge” and India’s “Great Wall of China”. Defining the south Asian sub-continent, its peaks intercept the clouds, sundering climatic zones, peoples, and lifestyles. By repulsing the monsoon of south Asia it denies to inner Asia the lushness enjoyed by India and condemns it to extremes of temperature and aridity. Immediately north of the mountains, trees are rare and the (Mongoloid) people are mainly graziers; immediately to the south the slopes are well forested and the (Aryan) people are mainly farmers and crop growers. A climatic barrier and a rampart against invaders, the Himalayas also control Asia’s life-support system. From the Tibetan plateau, which is swagged and supported by the Himalayas, 10 of the world’s largest rivers rovers plunge south and east, around and through the Himalayan wall, heading for the Indian Ocean and the Chinese Seas. On the book of these rivers (including the Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Irrawaddy, Mekong, and Yangtze), Asia’s civilizations were nurtured; on their floodwaters half the world’s population depends. To these people, drought apart and dams permitting, the frown on the face of our planet is mole like a benevolent smile. In the heart of these mountains lurks the peak we know as Everest. […] From the plains of northern India, the mountains appear (cloud cover permitting) as a long, serrated ridge of snowy peaks sublimely etched against the horizon. Closer acquaintance reveals something much more complex. The serrated ridges disappear behind a tangle of densely wooden outer ranges, and the glistening fangs, when glimpsed from closer quarters, present unfamiliar profiles. The Himalayan wall, some 2000 miles (3200 km) long, is about 300miles (480 km) wide, with its successive ranges so stepped that the highest peaks are always the furthest and often appear dwarfed by lesser peaks nearer at hand. In fact, just to reach the base of Everest from the plains, one must climb and descend several times its actual height, fording innumerable torrents in the process, removing hordes of highly intrusive leeches, experiencing extremes of temperature and precipitation, as well as suffering from the premature decrepitude (or worse) caused by oxygen deficiency. It is as if the mountains objected to trespassers.’[3]

Internal Links

- Dzatrul Rinpoche

- Khenbalung

- Lord of the Dance

- Miyolangsangma

- Ngawang Tendzin Norbu

- Rongpuk Monastery

- Tengboche Monastery

- Tengboche Rinpoche

- Thupten Chöling

- Trulshik Rinpoche

- Trulshik Dongak Lingpa

- Yangti Nakpo

Notes

- ↑ Stephen Venables, Everest Summit of Achievement, Royal Geographical Society, London, Ted Smart, 2003, p11.

- ↑ Stephen Venables, Everest Summit of Achievement, Royal Geographical Society, London, Ted Smart, 2003, p58.

- ↑ Stephen Venables, Everest Summit of Achievement, Royal Geographical Society, London, Ted Smart, 2003, p11.