Transforming Suffering into Love and Compassion—An Interview with Garchen Rinpoche

From View: The Rigpa Journal, July 2012

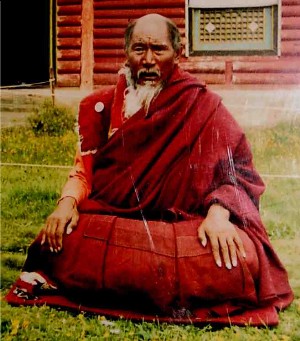

With a beaming smile and constantly spinning prayer wheel, Garchen Rinpoche visited Lerab Ling in 2009 to teach at Rigpa’s summer retreat. In this interview, he recalls the twenty years that he spent in a labour camp during the political turmoil of China’s Cultural Revolution, and explains how the experience helped him to deepen his understanding of the Buddha’s teachings.

Generally speaking, we are all in the same situation. All sentient beings in the three realms of existence are in the prison of samsara, and we all experience the sufferings of samsara. The Buddha said that the best way to overcome suffering is by understanding the two truths—relative truth and absolute truth. Even if you don’t have any particularly special qualities, if you understand the two truths, that will enable you to free yourself from your suffering—even your present suffering. It is important to realize that the suffering you are experiencing now is the result of karma, your past actions. To understand that already makes the suffering somewhat more bearable, because you see that it does not come from outside. Why am I experiencing suffering? Because of the negative actions I’ve done in the past.

And likewise now, I have all these negative emotions that rise in my mind, and cause me to commit negative actions, and so in the future I will experience further suffering. So whenever I experience suffering now, I know that this has been caused by the negative actions I have committed in the past, and that should really spur me on to do something about it, to work to eliminate the cause for further suffering, the destructive emotions, and so on. When suffering arises—say, for example, that you get sick—then immediately you should think, “Oh, this is purifying some negative karma that I have accumulated.” This is how to turn suffering into something that is much more bearable, and more positive. Through this understanding, when suffering comes, you are able to think, “This is good for me.”

As a practitioner with very little experience, I could perhaps begin to apply this advice to some small suffering, if I caught a cold or a minor illness, for example. But I would find it overwhelming if I was thrown in jail. Were you able to apply this immediately when you found yourself in a situation that for most people would be unbearable?

As I said before, you have to understand relative and absolute truth. To understand relative truth is to understand that things arise from causes. The result comes from causes. The suffering that we experience is the result of our karma, so first we need to develop a profound understanding of the law of karma—cause and effect.

To understand absolute truth is to see the nature of the mind. Mind in its nature is devoid of any suffering. Once we understand the nature of mind, we see that it is actually wisdom, and wisdom can eliminate even the most subtle thought of suffering. When we’re resting in the aspect of wisdom, whatever thoughts arise are liberated within the space of wisdom. This wisdom is such that, when you need to think about something, then you can think in a very precise way, have all the thoughts you need and be very precise, very sharp. But when you don’t need those thoughts, you can simply remain in the state of clarity, free of rising thoughts. With this realization of absolute truth, you are able to face suffering, and it becomes a more joyful kind of experience.

This is not so easy at the beginning. You need to have practised meditation and gained some stability. At the start, when you receive teachings and reflect on them, you can gain some understanding, but that understanding on its own won’t help you to deal with the more intense types of suffering.

When I went to the labour camp, by applying these two aspects of relative and absolute truth, I didn’t experience it as something painful and unbearable. But there were two men in the camp with us who killed themselves because they just couldn’t stand it. The suffering was way too much and they decided to put an end to their lives. But we never thought about that—in fact we were constantly joyful and happy. The people who put us in jail and called us all kinds of names were wondering: “What is it with them? Those lamas are always happy.” That comes from understanding relative and absolute truth.

When you experience suffering, what is taught is that you should immediately think about the suffering of others. You realize: “I am not the only one. Everybody else is suffering too.” When you think about the suffering of others, your suffering seems ridiculously small compared to all the suffering that there is in the world; and then what often happens is that you forget all about your own suffering.

The practice of cultivating bodhichitta is so important. First you think about all sentient beings, how they have been your father or mother in a previous lifetime, and the kindness that they have shown to you. As a result, you are determined to repay this love that they have given to you.

To put it simply, there is what we call view, meditation and action. The view is to realize that all sentient beings have been our parents at one time or another, and that they have been extremely kind to us. The meditation is wanting to repay this kindness, to really cultivate a deep feeling of love towards all those sentient beings. And the action is, whatever you do, to make sure that it is beneficial and helpful for others. The key point is to cultivate this love for others over and over again.

Which other lamas were in prison with you?

There were ten thousand prisoners, including about four hundred Tibetans from many different places, Golok, Amdo, Kham and even Lhasa. Among the many lamas were the great master Khenpo Munsel—who didn’t experience any kind of suffering when he was there—Adeu Rinpoche and Dodrupchen Rigdzin Tenpé Gyaltsen. I was in the same room as Dodrupchen Rinpoche before he passed away in 1961.

How were you able to receive teachings from Khenpo Munsel in that environment?

It was not easy, because we were always under surveillance and we had to work. But sometimes when I was sick, or pretending to be sick, Khenpo Munsel would come and share a few words of teachings with me, in secret. We were not allowed to have any texts with us in jail, so he would just teach me a few words at a time, so that I could remember them.

Khenpo Munsel stayed with six other lamas in one room. All of them had physical problems and could not work, so they were able to stay in their room and did not have so much fear of being discovered by the guards. They would sometimes come to check on them, but otherwise they were just left together in their room, and a little piece of bread or something would be left for them to eat. I was younger at the time, so I had to work about eight hours a day. At times, when I had a little bit of a break or when I was sick, I would receive some short teachings in secret.

How did you practise what Khenpo Munsel taught you?

We would receive the instructions from him and then practise them in secret, and then we would get further instructions. Of course, I could not sit cross-legged and practise, so I would practise when I was supposed to be sleeping. Sunday was the rest day, and I would stay in bed all day. When I was working, eating or interacting with others, I would always try to maintain mindfulness, awareness and vigilance. But when I was in bed, and on Sundays, I would recite my practices. I already knew how to practise before I went to jail because my father and uncle were both great masters, and they taught me from the age of ten. So by the time I went into jail at the age of twenty-four, I already had some knowledge of how to practise Mahamudra, tsa-lung, and so on. And of course, it was incredibly beneficial to meet Khenpo Munsel, because of the great lineage of blessing that he holds. So I would practise in this way from the time I entered jail, when I was twenty-four, until I was released, when I was forty-four. When I was released, along with the other lamas, I didn’t sleep for eight or nine years.

In the daytime, I would go about my activities, meet people, work and so on, and at night I would just practise, fall asleep a little, and then practise some more.

You must have seen a lot of suffering around you in jail. Were you able to help others physically, or was it something you could only practise mentally?

The main point is to cultivate an attitude of great love in the mind, because if you can do that genuinely, then that is of great benefit to others. Minds can make a connection. If you really have a loving attitude, then when you enter a room, people will be happy, and you will have a positive effect on them. When certain people call you on the phone, for example, it makes you happy, but when others call, it doesn’t have the same effect.

Why do sentient beings suffer? They suffer because of grasping at the self. When you give them love, they will also feel more open and loving towards you, and at the same time they forget about themselves. There is less self-grasping, and they suffer less. So this is the best way to overcome suffering. The best way to help others is to benefit their minds.

When you think of all sentient beings, who have been as kind to you as a loving mother, you forget about yourself. You abandon your self-grasping. This brings benefit to you and to others at the same time. Bodhichitta is the special teaching of the Buddha. We call it the ‘great love’, because it is a love for all sentient beings—even for enemies. When you love others, your own well-being will be naturally accomplished, because you let go of the cause of suffering: grasping at the self. When you give your love to somebody else, ego is not there, only the other person. By loving that person, you benefit him or her, but also yourself, since there is no self-grasping. So to love all sentient beings brings immense benefit. This is the love of the Buddha.

If you are really able to cultivate a loving attitude, then you will be of tremendous benefit in the world. This comes from the mind, and if more people develop that kind of attitude, it will be incredibly beneficial. That is why I’m always amazed whenever I hear that one person—let alone many—is staying on retreat, because just that one person will benefit so many sentient beings. This is the special teaching of the Buddha. By cultivating a loving attitude in this way, then we are able to benefit sentient beings on a vast scale.

If more people in the world were to have that kind of loving attitude, then there would be fewer problems. If, instead, you have anger in your heart, then you get involved in fights, arguments and things like that. If a group of people are able to cultivate a more loving attitude, then those who are angry will receive that love and think: “They are our friends, we won’t touch them. We won’t argue with them, we won’t fight with them. We can sort it out without fighting.” The problem is that, nowadays, there seem to be fewer and fewer people cultivating love, and more and more people cultivating anger, and that’s why there are more and more problems.

Did you not feel any anger or resentment towards the people who kept you in captivity?

At first, I was really, really angry with them, but Khenpo Munsel scolded me a number of times and told me I shouldn’t act that way. I was very upset because they did so many terrible things, not only to me but to others as well. So when I first went into prison I was really, really angry, and I tried to make trouble, but then Khenpo Munsel told me I shouldn’t be doing that. And once I understood that it is all the result of karma, I didn’t get angry any more. Towards the end, the guards were actually quite nice to me.

Could you say a little bit about Khenpo Munsel’s qualities? Are there any particular memories you have of him?

He was always the same. He didn’t have the slightest anger or negativity. He didn’t have an ordinary mind any more. From the moment he entered the jail, it was like he was on a different level from the others. He could do whatever he wanted, and the prison officers wouldn’t create any trouble for him. He had that kind of presence.

For example, there were six other lamas staying in a room with him, and one time they recited 100,000 Seven Line Prayers. The guards found out, and the lamas were extremely afraid that they would be in trouble. When the guards came in, the atmosphere was very tense, but as soon as they arrived in the presence of Khenpo Munsel, they seemed to forget what they wanted to do. Whenever they wanted to scold or beat them, simply by arriving in his presence that would just disappear.

Other people could do something very minor and get into so much trouble, but he could do pretty much whatever he wanted and the prison officers would not harm him. For example, when Khenpo Munsel was in jail, he said he couldn’t walk, and when they saw him, they said: “Ah yes, it must be true.” Whenever he went outside, people had to lift him, or he would push himself along on his hands, but he couldn’t walk, and the guards never questioned it. They trusted him, but they didn’t trust anyone else. Khenpo Munsel stayed in jail and didn’t walk for twenty years or more. And the day he was released, he walked.

I think many people, if they spent twenty years in prison as you did, would consider that twenty years of their life had been taken away from them. Do you look at it in this way?

No. It was not a waste of time. It was a purification of so much karma. So many died during those years. We lost a lot of people through warfare, famine and epidemics, but basically I managed to live through it all.

While we were in jail, we were practising, so we didn’t waste our time. Of course, if you don’t have so much understanding of the law of karma, cause and effect, then you might just focus on the suffering and the hardship you went through, and then those years would be wasted. But this was not my experience at all.

Do you have any heart advice for practitioners about how they can transform their suffering and cope with difficulties? Would it be to develop this loving attitude towards others that you described earlier?

You need to develop this loving attitude and also to practise tonglen, giving one’s happiness and well-being to others, and taking on their suffering. If you really have a loving attitude, the first thing you do is to take on the suffering of others. When you see someone you love or someone you know suffering, immediately you take on their suffering, and you give love and happiness to them.

That is what loving means on a spiritual level—a dharmic level, you could say. When you love someone in an ordinary way, you love them as long as they love you and are nice to you. And the day that person doesn’t love you as much, then you stop loving them and giving your love to them. That is the way it happens usually. Whereas the dharmic kind of love is to give love, happiness and well being, and take on the suffering of others, no matter what—even if the other person does the worst possible thing to you. You are always giving.

Translation by Gyurme Avertin